Cameras have always held a special fascination for me. Like the human memory, a camera can preserve a scene in detail, for a very long time.

I cannot look at an old camera without wondering where it's been, who's used it, and what it has recorded during its decades of use.

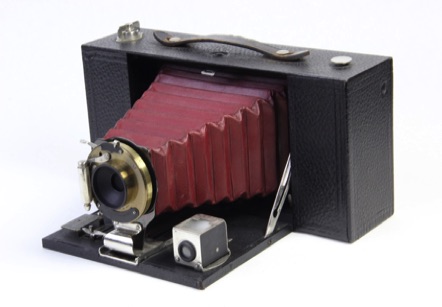

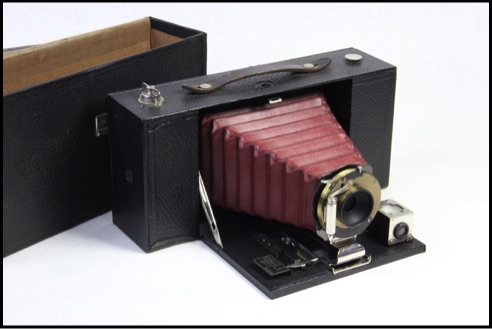

The first camera I played with as a child was a Kodak 3A Brownie, as seen in the Kodak ad. (left) It belonged to my paternal grandparents and had been carefully used to record special occasions for many years.

The 3A first appeared in 1909, and used a huge roll of film, which would dwarf the little 35mm rolls that came along several decades later.

At the time, the $10 price was lofty, to say the least. And with only eight pictures on a roll of film, users had to consider carefully what they shot.

Kodak's use of the name "Brownie" came from a popular children's cartoon character of the time, and from Kodak's supplier of early cameras, Frank Brownell of Rochester, NY.

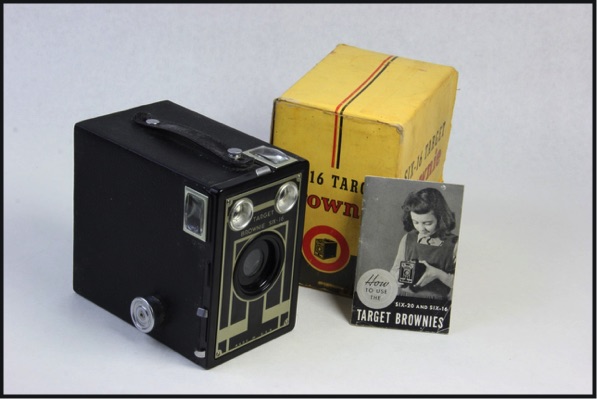

Perhaps the longest running single style of Kodak camera was the simple box type, which began in 1900 and originally sold for $1. Made mostly of cardboard, they were inexpensive, rugged and dependable.

Through the years, Kodak changed the model names of the basic design, but the camera itself remained very similar, with the trim being the main difference between most models.

The one pictured here is a Kodak Target Brownie Six-16, which was introduced in 1941.

This model and its many cousins, often differed only in the order of words in the name; i.e., "Target Brownie", vs "Brownie Target".

In later years, the name "Brownie" would reappear several more times.

As Bakelite became more popular for building inexpensive cameras, the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye Flash took the 1950's consumer camera market by storm.

Unlike its brothers and cousins, this model offered an accessory flash attachment that used a number 5 flash bulb, and featured a large plastic reflector.

It also sported rounded edges and corners, producing a much more modern look.

In 1950, the basic camera sold for $5.50. The flash model with the accessory flash unit sold for $15.

This camera used 620 film, which yielded 12 2-1/4" square negatives.

Interestingly, as this camera's production run continued, Kodak switched from a glass lens to plastic.

The first known photograph was made in 1816. It was a piece of paper coated with a special chemical, which was exposed to light via a simple hand made camera. For the ensuing 160 years or so, many improvements were made to that first camera design, but the basic principle remained the same: light directed through a lens to a chemically treated sheet which caused an image to be captured.

On this page we're going to concentrate on the evolution of still photography during the last century, as we look at some of the cameras that led us to where we are now.

The Baby Brownie appeared in 1939, and sold originally for $1.50. It was tiny compared to the big 3A Brownie, and it used a much smaller 127 roll of film.

The camera was molded from Bakelite, an early plastic material which was somewhat fragile, and would crack easily if dropped or mishandled.

This later version, (pictured), was also inexpensive, (see $2.75 price on box), and was simplicity in its most pure form.

Like it's many predecessors of the time, the little Baby Brownie required no focus or exposure adjustments. Just "point and shoot".

"YOU PUSH THE BUTTON, WE DO THE REST"

The most important contribution that George Eastman made to photography was his invention of roll film. Before that, photographic images were exposed onto glass or metal plates in a process that was far too complicated for most people to perform. The use of dangerous chemicals, including iodine and mercury vapor, added serious health risks to the procedure. Given the complexity of taking and developing the early images, it remained the domain of professionals until Mr. Eastman became involved.

Roll film changed all that, bringing multi-exposure picture taking to the masses in a form that was not only safe and affordable, but also relatively convenient. Plus, you could load Mr. Eastman's cameras anywhere, without a darkroom!

A PAINFUL DEMISE

For a substantial part of the 20th century, Kodak virtually owned the domestic photography industry. But in 1975 when one of its own engineers created the first experimental digital camera, Kodak management didn't fully comprehend the possibilities. Worse yet, fear that the new technology could ruin its core film business caused the digital development to proceed very cautiously. In spite of its timid approach, by 2005 Kodak digital cameras outsold all others. However, stiff competition from Japan soon overtook Kodak's dominance, and by 2010, their early market lead had tumbled to 7th place.

Meantime, as they had feared, the sale of film decreased, and in 2009, Kodak stopped production of 35mm Kodachrome film, ending seventy-four years for the very popular product, which had played a huge role in the acceptance of the 35mm format.

Sagging profits and a substantial drain from the employee's retirement program contributed to investor's demands for change. In 2011, the company's stock value had decreased by 90%. Frantic to raise much needed capital, Kodak tried to sell off its digital photography patents, but there were no takers.

In 2012 the company that brought affordable photography to most of the world filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. For those of us old enough to have used dependable, high quality Kodak products all of our lives, it was a very sad thing to witness.

REQUIEM

Slowly at first, then with increasing speed, digital technology presented an increasingly attractive alternative to film cameras. The ability to capture and store thousands of high quality images eliminated the inconvenience and cost of film. It gave amateurs and professionals alike the ability to shoot dozens, even hundreds of photos, just to get one really good shot. Photographers could instantly view their shots and reshoot as needed, completely eliminating the delay and guesswork of photo lab processing. Battery life improved, "outdated" film became a problem of the past, and digital cameras could calculate complicated exposure balance at the push of a button. Added to the many other assaults on the future of film, the "new" internet presented the ability to send digital images anywhere in the world, instantly, and without cost.

Another important driver of change was the appearance of photo editing software that would often repair digital images that, had they been on film, would have been unusable. Such software eliminated the use of time-consuming processes like airbrushing and negative retouching, tasks that once required considerable time and skill to do well.

More recently, the inclusion of high quality cameras in cell phones has weakened a substantial segment of the camera market, bringing added credibility to the saying, "The best camera you have is the camera you have with you".

There is, however, the lingering interest in, and appreciation of, the "film look". Because film photography involves a complicated combination of various factors, a photochemical image is very different from a digital one. That difference remains so popular that editing software and some cameras now offer filters to apply the "film look" to digital images.

Thus we may find truth in another much older saying: "The more things change, the more they stay the same".

TRIVIA

George Eastman had a strong sense of identity for his product brand. With his mother's help, he created the word Kodak, feeling that it was an easy word to pronounce, and wouldn't be confused with other names. It started with a "K", a letter he felt portrayed strength. Mr. Eastman believed the name should also be visually recognizable, so, he came up with his first company trademark, which appeared on many of his early cameras.

Since the early consumer cameras had shutters that would fire independent from the film advance, photographers had to remember to "wind the film" after each exposure. Because of this requirement, double exposures and blank frames were a common occurrence. With the appearance of the 35mm camera, advancing of the film also cocked the shutter for the next shot, so double exposures and blank frames were automatically avoided.

The roll film had a layer of paper wound with it. The paper served to protect the film from unwanted light exposure and also provided a series of printed numbers to allow the user to advance the film and see the number in a little red filtered window on the back of the camera. There was a downside, however, because when the film was advanced in the camera or separated from the paper during development, a static discharge, (small spark), could damage exposed images. Static damage also threatened the 35mm casette as the film was advanced, or if it was dropped. In 1962, Kodak was awarded a patent covering a chemical coating that would protect film from static discharge damage.

During the 20th century, Kodak filed just under twenty thousand patents.

In 1895 the Pocket Kodak was launched at a price of just $5. It's small size meant it could be carried in a coat pocket. Many of the photographs taken during World War I were taken by that camera in the hands of servicemen.

SOME CAMERAS FROM MY COLLECTION

The first digital camera was built by Kodak engineer Steven J. Sasson between 1973 and 1975. Because of it's size and the very long exposure time required to register an image, the device was relatively useless from a practical standpoint. But the concept served as a major milestone in the future of photography, and later in cinematography.

Oddly enough, Sasson's invention would eventually spell the demise of the popular use of Kodak film, and to an extent, the demise of Kodak itself.

So it was that this device, the size of a bread box, would alter history in ways no one could have possibly realized at the time.

And equally odd, very few people remember the name Steven J. Sasson.

CAUTION! MAJOR CHANGES

AND A ROUGH ROAD AHEAD!